A coronavirus vaccine rooted in a government partnership is fueling financial rewards for company executives

As shares of biotech firm Moderna soared in May to record highs on news that its novel coronavirus vaccine showed promise in a clinical trial, the nation's senior securities regulator was asked on CNBC about news reports that top executives had been selling their stock in the company.

Jay Clayton, chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission, responded that companies should avoid even the appearance of impropriety. "Why would you want to even raise the question that you were doing something that was inappropriate?" he said.

Notwithstanding Clayton's statement, there is little public evidence that company leaders slowed their stock selling. Now, corporate governance experts and some lawmakers say the trades could cast a shadow over Moderna, one of the biopharmaceutical industry's most remarkable stories. The questions come as the 10-year-old company is leading the race in the United States for a coronavirus vaccine - a feat rooted in a government partnership formed years ago that could change the path of a disease afflicting the world.

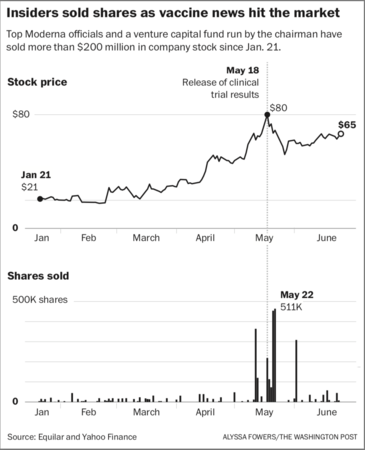

In total, seven corporate executives and board members as well as a venture capital fund run by Moderna's board chairman collectively sold almost $101 million following Clayton's comments. The trades were part of more than $200 million in sales by insiders since Moderna announced Jan. 21 that it was pursuing a vaccine in partnership with the National Institutes of Health. That's according to an analysis of SEC filings that the national executive compensation research firm Equilar performed at the request of The Washington Post - the first such comprehensive examination of the company's stock sales this year.

Insiders selling included Moderna Chief Executive Officer Stéphane Bancel, Chief Financial Officer Lorence Kim and Chief Medical Officer Tal Zaks. The trades were preprogrammed, according to the company's required public disclosure filings, meaning they were made in accordance with a predetermined schedule or triggering event such as a share-price threshold. Moderna said it will not disclose any details of the preprogrammed trading rules for its executives.

On May 21 and 22, the co-founder and chairman of the company, Noubar Afeyan, reported selling $68 million worth of stock held by Flagship Pioneering, the venture capital fund he founded that is Moderna's largest shareholder. Afeyan did not sell any of his personal stock holdings in Moderna, according to Flagship and public filings. These trades were not preprogrammed, according to the company's public disclosures.

Moderna's stock rose by 200 percent from January to June - as company news releases and news reports described early progress in its quest for a vaccine. In May, it was up as high as 300 percent after the release of the results of the clinical trial. The company made a public offering of stock on May 18 at the very peak of its share value.

Federal securities law requires officers, directors and large shareholders of publicly traded companies to report their trades in company stock to the SEC. Companies typically prohibit sales of stock by executives for 180 days after the initial public offering, specialists said.

The very first insider stock sales reported at Moderna occurred infrequently last fall, with the first in September 2019, 10 months after the company went public in a record-setting IPO in December 2018. Bancel began routinely selling shares starting in the fourth quarter of 2019 under his preprogrammed plan. The pace of selling picked up among Moderna's other executives in 2020, according to the public filings.

"Executive sales are made under preplanned 10b5-1 plans, which are entered into during open trading windows in accordance with the company's insider trading policy,' " said company spokesman Ray Jordan in an email. "As a matter of practice, Moderna does not intend to comment on any alleged or potential litigation or investigation; nor on purchases or sales by individual executives, investors or groups."

Moderna did not make company officials available for interviews.

Bancel has a "long-term commitment to Moderna and to the development of the . . . technologies being developed by the company," which he joined as its second employee nine years ago, Jordan added. "He has liquidated a small portion of his holdings each month through a planned 10b5-1 selling program. . . . Substantially all of his family's assets remain invested in Moderna."

The company has nearly 150 employees who operate under 10b5-1 plans, he added.

Flagship spokesman Gregory Kelley said in an email that the fund's stock sales, which were not preprogrammed, "were made in accordance with [Moderna's] policies and during an open trading window as determined by [Moderna's] general counsel."

Experts in securities law say the rules for preprogrammed stock trading plans are ambiguous enough that executives could gain unfair advantages, particularly when it comes to their control over the timing of release of market-moving data, and deserve scrutiny. The sales at Moderna in May raise potential concerns, the experts said.

"All of the activity in the days leading up to the announcement and the offering, and the days following the announcement, are ripe fodder for SEC investigation," said Jacob Frenkel, a former top SEC investigator now in private practice as chair of government investigations and securities enforcement at the law firm Dickinson Wright. Frenkel said a likely subject of scrutiny would be what policies Moderna has for "blackouts" on executive trades during major news events and whether such policies were followed. The company said blackout dates are included in its insider trading policies, but the dates are not public.

The SEC said it would not comment. The agency typically does not publicly disclose whether it is investigating a company.

Nell Minow, an expert in corporate governance and vice chair at ValueEdge Advisors, said it is inadvisable for Moderna's corporate insiders to be selling stock, particularly in the midst of major news about its leading product.

"It can send the market a signal that is opposite to all of the positive things that they are trying to communicate," she said. "By definition, it is very concerning.

"Whether it is preprogrammed or not, it's hard to believe that anybody who thought the company was going to be tremendously successful with this vaccine would be selling," Minow said.

Harvey Pitt, a former SEC chairman who now heads Kalorama Partners, told CNN in May that the timing of the trades was "highly problematic" and that the SEC should review communications inside the company to find out "what was going on in people's minds before all these transactions."

Bloomberg in May estimated Bancel's stake in the company as worth more than $2.2 billion, when measured at Moderna's peak stock price. He has sold about $17 million worth of shares since Jan. 21, according to the Equilar analysis. Flagship's 11 percent share of the company was worth $3.2 billion, Bloomberg said, and its sales of Moderna stock represented about 2 percent of that value. Given the large value of those holdings, the relatively small value of stock sales does not raise a major concern, said Jesse Fried, a Harvard Law School professor and expert on executive pay and insider trading.

"You don't want to be exploiting a crisis to make money, but the truth is that any company that is going to sell the vaccine is going to be making money on the crisis," Fried said, "and that's great, because we want to incentivize people to wake up early in the morning and stay in their labs late at night coming up with something that will help us."

But the Moderna sales are triggering political debate.

"Moderna executives used this opportunity to capitalize on the covid-19 crisis, and to add insult to injury, the value of their stocks increased based on the taxpayer-funded investment in the development of the vaccine," Sen. Chris Van Hollen (D-Md) said in an email. Van Hollen is the sponsor of legislation that would require the SEC to revisit its rules for preprogrammed insider trades.

- - -

The enormous success of Moderna shows how pharmaceutical companies, often with help from the government, can achieve fantastic results even without delivering a product to market.

Its speedy response to the covid-19 pandemic was enabled by its vaccine technology based on messenger RNA, which carries genetic codes instructing human cells to produce what is known as a "spike protein" molecule. The spike protein, which was invented jointly by scientists at the National Institutes of Health and the University of Texas at Austin, triggers the immune system to create antibodies against the coronavirus. The technology allowed Moderna in March to become the first company to test a vaccine in a human, just 66 days after the coronavirus genetic code was published.

On May 18, Moderna announced partial clinical results from 45 human test subjects suggesting the vaccine was safe and triggered an immune response. It said it measured neutralizing antibodies in eight test subjects, which was seen as early evidence that its vaccine may work. The news release did not contain detailed data from the patients in the trial, and crucial test results on some subjects were not available at the time the release was issued.

The news drove the share price to a record peak of $80. On that day, the chief financial officer, Kim, who is leaving the company in a previously planned departure, sold $19.5 million in shares in preprogrammed trades, according to public filings. In all since Jan. 21, Kim sold $54 million in shares, according to the Equilar analysis. As of June 2, he still held $70 million worth of shares.

Minutes after the end of trading on May 18, Moderna announced it would issue $1.3 billion worth of new stock at $76 per share. The company said cash from the offering would be plowed into coronavirus vaccine manufacturing, including hiring 150 new production staff, as well as other company priorities. But as the stock dropped from its peak in subsequent days and weeks, plaintiff lawyers quickly announced that they would prepare class-action lawsuits, suggesting that the company's news release overhyped the data.

Moderna said it "worked cooperatively" with NIH on the content of its news release and expects NIH to make detailed data from the Phase 1 trial public at a later date. NIH confirmed that it reviewed the data in the news release and said it was accurate.

The chain of events in the midst of the pandemic has generated negative attention for a company that is competing with much larger corporations - including Pfizer, Merck, Johnson & Johnson, and AstraZeneca - to develop the first coronavirus vaccine.

Unlike those companies, Moderna has no approved products and zero revenue stream from sales, according to the company's disclosure reports. Fifteen drugs in its pipeline, ranging from virus vaccines to heart treatments and a cancer vaccine, are still in early or mid-stage development.

The company is built on the notion that cells inside the body can produce drugs and vaccines, if they are directed to do it by delivering the messenger RNA directly into the cells. Investors are wagering that Moderna's technology will work for other medicines down the road, including more viral targets and a cancer vaccine, say drug industry specialists.

"If it works for this one virus, you can bet that it works for many, many others . . . and that kind of franchise will be incredibly valuable," said Andrew W. Lo, the Charles E. and Susan T. Harris professor of finance at the MIT Sloan School of Management, who does not have holdings in Moderna but who has personal investments and financial ties to other biotechnology companies and biotech venture capital funds.

- - -

The Cambridge, Mass., company, founded in 2010, has attracted more than $5 billion in private-sector investment, according to company figures, including partnerships with Merck and AstraZeneca, multiple rounds of venture capital financing, and public stock offerings worth about $2.5 billion. The company has $483 million in government commitments to develop a coronavirus vaccine but said it has not tapped the money yet. Over its history, Moderna has received about $77 million in funding for various projects, the company said.

Moderna's rapid response gave it a leg up in the markets. Older vaccines relied on deactivated or weakened virus, grown in chicken eggs, in a slow process. The new breed of RNA vaccines like Moderna's can be designed on computers based on the genetic code of the virus and manufactured quickly. Pfizer also is working to develop an RNA-based coronavirus vaccine and began a Phase 1 trial in May.

Still, the delivery system needs to be proved safe and effective in large numbers of people.

"There is not a single drug approved with this technology. This is really the bet we are making, that all this is going to work," said Otello Stampacchia, the founder and managing director of Omega Funds, a life sciences venture capital firm in Boston.

- - -

The foundation of the Moderna vaccine was laid years before a mysterious respiratory illness was reported in Wuhan, China. In 2012, another deadly coronavirus, Middle East respiratory syndrome, jumped from camels into humans. Barney Graham, the deputy director of the federal Vaccine Research Center, which is part of NIH, said in an interview that he wanted to use cutting-edge technologies that examined the precise shape of a virus - down to individual atoms - to design a vaccine against the threat.

But Graham and academic collaborators had to solve a problem. The target the scientists were interested in - the distinctive spiky protein on the virus surface - was unstable and tended to shape-shift.

Nianshuang Wang, a postdoctoral researcher then at Dartmouth, spent months trying to identify genetic mutations that would stabilize the shape-shifting spike protein, eventually finding a solution that worked in multiple coronaviruses. The paper, published in 2017, took persistence to publish - it was rejected five times.

"People generally at that time said, 'Coronavirus is not a big concern,' " Wang said. "They didn't get the idea that this can be a great technology in the future, to prevent another coronavirus pandemic."

Graham was interested in using new technologies to speed up MERS vaccine development and in October 2017 began working with Moderna. The company's technology could deliver messenger RNA to normal human cells that instructs them to churn out the spike protein with the crucial mutations. The presence of the spike protein in the body triggers the creation of antibodies against the virus. But with MERS sparking only small, occasional outbreaks, it wasn't until January 2020 that the approach drew the world's attention.

Even before anyone knew for certain what was causing a mysterious pneumonia in Wuhan, Graham and Bancel began talking about working together. Graham also called Wang's boss, Jason McLellan, now at the University of Texas at Austin, to see if they could design a stabilized spike protein that could be used in a vaccine.

Researchers in Graham's and McLellan's labs designed the protein through computer modeling in a single weekend. Moderna scientists helped finalize the genetic sequence for the vaccine platform they had spent years developing. Within days, the company began producing the coronavirus vaccine in a factory south of Boston. The NIH and UT Austin teams filed a joint patent application on the mutated spike protein. Moderna has a "nonexclusive" license to the protein, which means that NIH can license it to other companies, NIH said.

In record time - 66 days after the genome of a never-before-seen virus was posted on an online server - the first doses were injected into human beings through a clinical trial supported by more than $700,000 in federal funding. Moderna announced the beginning of a Phase 2 trial in May and said its Phase 3 trial in 30,000 subjects is scheduled to start in July.

Bancel has said it may be known whether the vaccine works by Thanksgiving - a view echoed in an interview with Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

McLellan said that his laboratory has created a second version of the spike protein that is even more potent and that it has already signed an agreement with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to ensure global access, which will enable companies with different technologies the ability to test and further develop potential covid-19 vaccines.

Two months after the first human subject was dosed with the Moderna vaccine, the public got its first glimpse of its potential effectiveness.

Before stock markets opened on May 18, Moderna issued a news release with positive but preliminary results of its Phase 1 safety trial. Eight trial subjects who received the vaccine had virus-fighting antibodies in their blood at levels similar or greater than people who have recovered from covid-19. Another 37 had promising immune responses, but tests were not available to see whether they had neutralizing antibodies.

As soon as markets opened on May 18, Moderna's stock jumped. By the close of trading, it had risen more than 20 percent. But Moderna was criticized for releasing limited data by Fauci in an interview published by Stat on June 1.

"I didn't like that. What we would have preferred to do, quite frankly, is to wait until we had the data from the entire Phase 1 - which I hear is quite similar to the data that they showed - and publish it in a reputable journal and show all the data," he told Stat. "But the company, when they looked at the data, as all companies do, they said, wow, this is exciting. Let's put out a news release."

Two days later, Bancel offered an explanation for the company's actions. A concern about leaks drove the decision to issue early information, he said in a June 3 video hosted by the Wall Street investment banking firm Jefferies that was publicly posted online.

Moderna had received preliminary data from NIH, which sponsored the Phase 1 trial, on May 14, Bancel said. The next day, Moncef Slaoui, a Moderna board member who had just left the company to go to the White House and assume leadership of President Trump's Operation Warp Speed initiative to develop vaccines, expressed confidence in a Rose Garden news conference that a vaccine could be ready by the end of 2020. Slaoui said from the lectern that he had just seen positive data from a vaccine manufacturer. Slaoui did not identify the trial or manufacturer.

Moderna determined that too many people knew about the data, Bancel said, and that the company needed to publicly release limited results to level the playing field for all investors.

"I have no idea if tomorrow it's going to be tweeted by somebody, it's going to be mentioned at a conference, on TV," he said. "That's a risk our legal team said you cannot take."