Crumbs from a cradle of mankind

Locals in Java scrabble for a living in the world's largest treasure store of prehistoric human fossils

Sangiran in Central Java first came to the world’s attention in 1934 when German paleontologist GHR von Koenigswald unearthed a treasure store of prehistoric human fossils here.

But while the discovery of the world’s richest human-fossil trove has made it a site of global scientific importance, Sangiran’s fruit has yet to benefit the people who have long lived on its land.

“So far, around 80 individual prehistoric human fossils have been found – over 50 per cent of all such fossil finds in the world,” says Harry Widiyanto, the head of the Sangiran Early Man Site Preservation Centre, about 15 kilometres north of Surakarta (Solo), Central Java.

“Some 13,000 fossils are stored in the Sangiran museum and their numbers are increasing,” Widiyanto adds.

Our ancestor Homo erectus occupied the Sangiran region in the early to middle Pleistocene era, from around 1.8 million years ago. They came to Java from Africa, leaving the continent 2.5 million years ago and settling in Sangiran after the land bridge had receded.

According to the fossil record, tortoises, elephants, pigs and monkeys also lived near the site around 1.7 million years ago and served as the basic food of our early forebears, supplementing healthy portions of local plants.

The three-storey museum keeps over 3,000 fossils of Homo erectus, land and sea animals and vegetation, in addition to rocks and sediment dating as far back as 800,000 years ago.

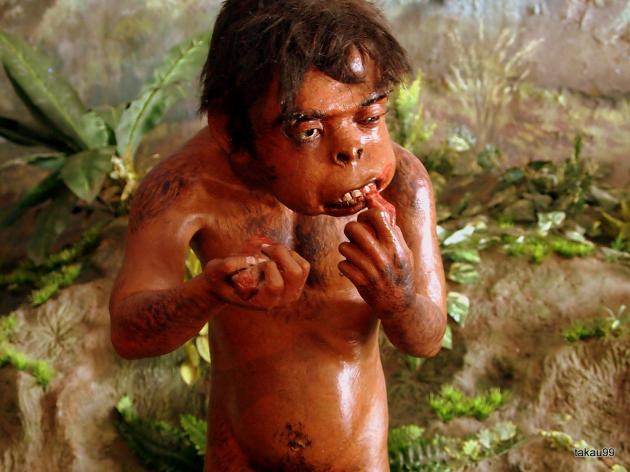

The exhibits include fossilised bull horns, elephant bones and crocodile skulls and a diorama showing the life of Homo erectus in Sangiran 500,000 years ago. There’s also a model of the so-called Flores man based on the work of Elisabeth Daynes, Widiyanto and Dominique Grimaud-Herve.

In the years before Sangiran became a tourist attraction, locals were free to roam the site and keep any fossils they found. They quickly discovered that their finds could command astounding prices.

The site was a veritable gold mine for locals, who sold fossils taken from barren farmland for tens of millions of rupiah.

Unsurprisingly, illegal trade in the artefacts flourished.

Eventually, residents were required to donate their finds to the museum in exchange for nominal compensation, but the meagre size of the reimbursement and the long time needed to obtain it meant the black-market trade continued to thrive.

“Locals were connected with would-be buyers by go-betweens. If they agreed with the price offered, payment was made right away,” says Wardoyo, a local resident of Sangiran.

Then in 1992 the government cracked down with harsher punishment for illegal trading in cultural heritage objects. As a result, the fossil trade began to decline.

Locals face further hardship due to the ban on farming their fossil-rich land. “We’re forbidden to cultivate the land. In return, we get training in making stone handicrafts, early-man statuettes, key-ring ornaments, fossil replicas and T-shirts as souvenirs,” says Sulastri, a resident of Krikilan, Sangiran.

Locals used to have to wait up to three months for as little as 200,000 rupiah (Bt620) compensation for their finds, says Widiyanto. But things have improved in the past few years after the museum was brought under Culture Ministry control.

“Recently we paid Rp10 million in compensation for a fossilised bull skull. We’ve also paid Rp2 million and Rp4 million for other fossil finds. If the objects are left in situ by their finders, the compensation can be greater” says Widiyanto.

He says the ban against cultivation of land near the museum was meant to protect the historical legacy and scientific importance of Sangiran.

“This site is now considered to be in a damaged state, because about 80 per cent of the zone has been exploited by locals. Such harm should be ended.”

In exchange for the cooperation of locals, the museum offers them training, Widiyanto adds.

“Oysters and sea pebbles can be processed into handicrafts, as they’re abundantly available – but the discovery of artefacts and fossils must be reported.”

For the last two years, 75 craftspeople have come together to establish the Sangiran Creative Economic Group, a cooperative with 20 rent-free kiosks. But poor product quality is putting off potential buyers.

“The museum shouldn’t just provide training but also aid us with equipment. So far, we’ve only been offered opportunities. We need capital. With limited capital, we can’t afford to buy modern tools,” says Kirman, a stone craftsman.

Krikilan village head Widodo says that locals haven’t yet fully benefited from the Sangiran site. For example, the Rp800 million collected annually in museum ticket sales, parking and toilet fees continues to be managed by the local tourism office.

“The village road leading to the museum is severely damaged. A good road would bring advantages to local residents as well as the museum,” remarks Widodo.

Meanwhile, locals say they can’t benefit from their barren land and can’t even use its clay to make bricks or roof tiles.

“The museum and regency administration hasn’t yet seriously involved local residents in managing tourism in Sangiran,” Sulastri says.

“We’re not satisfied.”

RELATED