How the world first saw Siam

King Mongkut perhaps found Scottish photographer John Thomson a refreshing change from the diplomats and missionaries

SCOTTISH PHOTOGRAPHER John Thomson saw Siam on the eve of its modernisation in the mid-19th century and his widely published images of King Mongkut (Rama IV) – and from China, which he also visited – are fairly well known.

Rarely seen, though, are his pictures of the ordinary Siamese of the Central Plains, but the National Gallery in Bangkok amply makes amends with its exhibition “Siam: Through the Lens of John Thomson”.

A large number of Thomson’s photos from the Wellcome Library in London – printed straight from Thomson’s glass negatives – are on view through February, many in startling scale and high definition.

This was a kingdom that, despite its misgivings about the coming of the Westerners, was finding a way to combine Buddhist thought and European science, tradition and modernity.

“Collectors of vintage photos will be familiar with some of the photos of King Mongkut, but many of the other photos have rarely been seen before, especially the photos of ordinary people and the developing urban landscape,” says Paisarn Piemmettawat, who wrote the book accompanying the exhibition. Narisa Chakra-bongse provides the English translation.

Born in Edinburgh in 1837, Thomson studied the emerging science of photography with the optics pioneer James Mackay Bryson. In 1862 he travelled to Singapore, where his brother had set up business, and established a photo studio. In 1865 he sold the studio and travelled to Siam on the Siamese steamer Chao Phraya, arriving in Bangkok that September and settling in for a three-month stay.

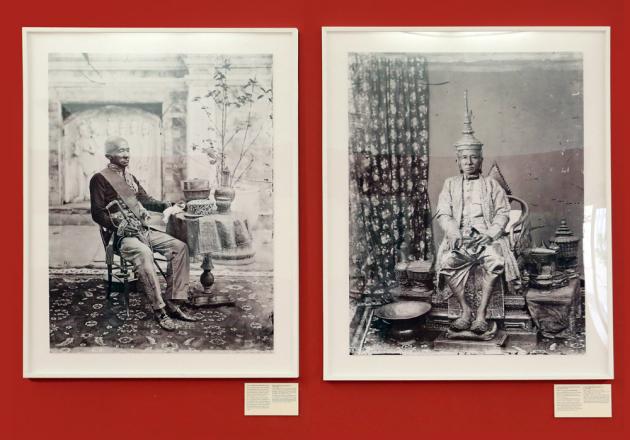

Thomson was granted access to the royal court and photographed King Mongkut, his children, royal ceremonies and government officials.

“Many of these photos were taken outdoors but props were arranged that made it look like they were taken inside the palace,” says Paisarn. “The images are quite clear, but none of them have any shadows at all, which looks strange.”

Beyond the guarded confines of the court, though, Thomson found compelling subjects among the commoners and monks, the temples and other attractions. He also travelled to what is now Cambodia to photograph Angkor Wat and the Bayon Temple, and to the coast of China.

Thomson used the “wet collodion process”, with glass plates tinted brown on one side with collodion (pyroxylin dissolved in alcohol and ether) placed inside the camera. It required him to carry everywhere all the cumbersome trappings of a darkroom.

The Scotsman was delighted to receive permission from the palace to photograph King Mongkut on October 6, mere weeks after his arrival in Siam.

“A shrill blast of horns heralded the approach of the King and caused us hastily to descend into the court,” Thomson wrote of the occasion. “His Majesty entered through a massive gateway, and I must confess that I felt much impressed by his appearance, as I had never been in the presence of an anointed sovereign before. He stood about five feet eight inches, and his figure was erect and commanding; but an expression of severe gravity was settled on his somewhat haggard face. His dress was a robe of spotless white, which reached right down to his feet; his head was bare.

“All was prepared beneath a space in the court when, just as I was about to take the photograph, His Majesty changed his mind, and without a word to anyone, passed suddenly out of sight. We patiently waited, and at length the King reappeared, dressed this time in a sort of French Field Marshal’s uniform. The portrait was a great success, and His Majesty afterwards sat in his court robes, requesting me to place him where and how I pleased.”

In the photo of the King in the field marshal’s regalia, he wears the sash of the Legion d’honneur and the Star First Class presented to him on behalf of Emperor Napoleon III by the admiral of the French fleet in Indochina. On a side able rests a small telescope, reflecting the king’s interest in astronomy and its Western means of study.

Through this and other pictures of Mongkut published in the Illustrated London News and L’Univers Illustre, he and his kingdom became much better known in the West. Few readers had ever had a glimpse of the ruler of faraway Siam. “They saw us as people who dressed well, a civilised people, a civilised country,” Pairsarn points out.

Scholars have said that Thomson was so well received in the court that the king became his patron. It was perhaps a refreshing change for the monarch to have a Western visitor who was neither a diplomat nor a missionary. Thomson’s only agenda was obtaining charming keepsakes.

King Mongkut was, of course, quite open to foreign culture, stemming from the empathy he gained during his 27 years as a monk prior to his accession to the throne. An educated man, he was curious about the world.

Thomson was thus able to attend royal ceremonies that were usually off-limits to Westerners, and the king also facilitated his journey in January 1866 to Angkor in Siem Reap, then still part of Siam.

In Bangkok Thomson was also able to take portraits of Crown Prince Chulalongkorn, who would become King Rama V, and Chao Phraya Boromma Maha Sri Suriyawongse (earlier known as Chuang Bunnag), who served as regent for five years between the reigns.

What Thomson found beyond the palace walls is perhaps best encapsulated in his picture of an anonymous Bangkok lad, a true vision of innocence. There’s another gripping image of an oarsman on the river teeming with vibrant life. Both subjects share the same hairstyle – and both seem baffled by the odd contraption pointing at them.

Thomson travelled to Ayutthaya and Phetchaburi as well, but it’s his shots of the capital that speak volumes about Siam in transition. The highlight here is a panorama taken from high up the towering prang of Wat Arun. The image is displayed side by side with a photo that Paisarn took recently from the same spot. The changes evident in the city are dramatic.

Paisarn notes that few people have ever seen Thomson’s pictures of the Golden Mount under construction either. In the foreground, a woman sits on a bamboo raft next to a boat laden with fruit. “There’s a long-stemmed durian in the boat – can you see how long we’ve been eating this type of durian in Bangkok!”

Thomson was back in England by 1872 and a decade later Queen Victoria named him official photographer to the British royal family, but while in China he’d developed an abiding interest in the common life of the

street. His images of Victorian London demonstrate his maturity as a photographer. He is no longer the pioneer

who explored exotic Siam.

The writer can be contacted at [email protected].

TIMES

CHANGE

n “Siam: Through the Lens of John Thomson 1865-66” is on view at the National Gallery until February 28. It’s opens from 8.30am to 4.30pm from Wednesday to Sunday.

n The book by Paisarn Piemmettawat is published by River Books and is available in most bookstores.