SPECIAL REPORT: Forest rangers risk lives for a pittance

Park defenders deserve better pay and welfare benefits for policing country’s resources, say experts

50-year-old Sutheerat Butpetch, a long-time forest ranger of Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary, would not have been standing in front of his colleagues and forestry executives to receive applause this week, if a bullet fired by an illegal logger last year had pierced his heart.

During an attempt to arrest foreign illegal loggers near Pang Sak forest protection unit of Mae Wong National Park, Sutheerat was shot in his left shoulder, but still considered himself fortunate as the bullet stopped short just under his flesh.

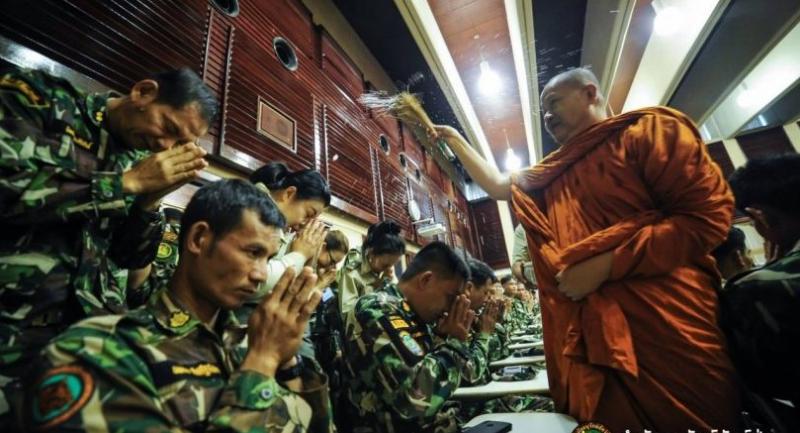

At the World Rangers Day event, Sutheerat along with 13 other forest rangers managed to come and collect honourable certificates to mark their bravery and dedication. However, 10 of their colleagues were honoured posthumously as they lost their lives in the line of duty over the past year, leaving family members or bosses to collect the recognition and certificates on their behalf.

“If there was any support that I wished to see more of, it would be some job security that many of us still lack. Last, but not least, is the support for our families so that we do not have to be worried about them if we suddenly leave them one day,” said Sutheerat, who has served Huai Kha Khaeng, the World Heritage site, for 26 years and is now a senior patrol ranger against forest crimes.

Risky job

Sutheerat is among some 20,000 forest rangers (Pitak Pa) from three departments – the National Parks, the Royal Forestry, and the Marine and Coastal Resources – under the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment (MONRE), whose job levels are ranked among the lowest.

They have less job security and state welfare than other government officials’ at the same departments, despite their risky job protecting forests, which is increasingly challenged by various threats, including poaching and illegal logging gangs equipped with heavy weapons.

As recorded by the DNP, over the past four years, 42 rangers have died_several from clashes with poachers, 13 were severely wounded, and 36 have been injured while carrying out duties.

Such low work status is a result of big changes in the country’s bureaucratic structure in the early 2000s, when permanent government official positions were capped, and contract based positions were introduced, following the preference of privatisation by the Thaksin government.

The measures have continued until now, resulting in a number of government workers, including forest rangers, seeing their work status considered merely temporary, contract based.

Their temporary work status leaves them with little or no job security, state benefits, or welfare coverage, and that has posed diffficulty for forest rangers to take care of themselves and their families.

Several sectors have been attempting to provide them support, especially on welfare issues, but still, the measures are seen as inconsistent.

Binding the differences

In his early career, Sutheerat was just a yearly contract-based forest officer (Panak-ngan Jang Mao), but he was later able to become a four-year contract-based forest officer (Panak-ngan Ratchakarn).

At present, the two positions receive slightly different state benefits and welfare. For a four-year contract, forest officers like Sutheerat receive more than Bt10,000 salary per month. Given their work status, they are able to access marginal social security coverage for medical treatments, like other workers in the country.

However, a number of Sutheerat’s colleagues who are still yearly contract-based officers (the DNP gives the number at around 8,400, while the RFD gives the number at around 1,700) would get a salary of Bt7,500 to Bt9,000 per month. And for medical treatments, they do not have social security coverage but must rely on the same Bt30 public health care card, as ordinary citizens.

Realising that their officers are at risk while on duty and in need of welfare coverage, the DNP and the RFD have been working to improve welfare for forest rangers. While the DNP has put a welfare fund in place to help support its rangers (Bt 30,000 in case of deaths, and Bt 10,000-20,000 in case of injuries), the RFD has introduced a new regulation to ensure welfare is set for its rangers as well (Bt 50,000 in case of deaths, and Bt 10,000-30,000 in case of injuries).

Over the years, other organisations including the notable Seub Nakhasathien Foundation, set up following the death of Huai Kha Khaeng chief, Seub Nakhasathien in 1990, and Pitak Khao Yai Foundation have been providing welfare support to the rangers.

The MONRE has also recently set up a new forest ranger welfare foundation to provide a short-cut to welfare for rangers.

Most of them, however, are still considered as not yet being state bound, but rather voluntary driven, posing inconsistency and unsustainability to their provisions of welfare, some forest experts said.

Khwanchai Duangsathaporn, a member of the natural resources and environment reform committee, said that the Pitak Pa have both job security issues and welfare issues needing to be addressed.

While they have similar duties in protecting the forest, these forest rangers have different contracts, resulting in different work statuses, state benefits and welfare.

Khwanchai said that it’s the government’s policy to cap its workforce, so job security improvement is an uphill task. Welfare, on the other hand, would be easier to improve, Khwanchai said.

Most of the welfare schemes provided, however, are not yet state bound, but rather voluntary, Khwanchai said, so, there is a need to make it compulsory.

The reform committee, he said, has been working to address the welfare issue for these people, and it has proposed in the reform plan to amend the National Parks Act as well as related laws to allow the departments involved to use income collected from their parks to support their rangers’ welfare.

The new welfare system, via legal mechanisms or policies, must be developed and put in place, to offer welfare to these people to a degree no less than other government officials, Khwanchai added.

“Welfare is not something to ask for, but should be institutionalised by law or policies. These people are at the frontline of forest battles, and actually talking only about the welfare provided is not enough. We need to talk about their established authority being brought in line with wrongdoers’ capacities, as well as protection to ensure their safety,” said Khwanchai.

Structural change

On the fourth floor of the DNP’s forest protection and suppression bureau, Sompoch Maneerat, a director of the agency’s administration system development group, is at a crossroad.

As a former chief of Huai Kha Khaeng himself, he realised how important job security is to his rangers. But as the job positions and the budget remain capped, it is not an easy decision to upgrade the forest officers’ positions from a low level to more permanent ones.

If the budget remained the same, upgrading positions for some could mean others suffer a loss as their salaries and benefits would be reduced to pay for those who receive the upgrade, affecting the whole workforce.

In the view of Sompoch, who is assigned to restructure the DNP and now drafting the plan, increasing or upgrading the workforce on its own would never be able to compete with the needs for protection of the forests, which have been increasingly challenged by various threats.

The whole work process of the department needs to be restructured so that it could respond to the present challenges – and that would help to also resolve the workforce problems the department faces.

As Sompoch sees it, the department, which is responsible for overseeing about 70 million rai (11 million hectares) in protected forests throughout the country, has a structure based on functions, while the reality is that its work is area-based. Some functions, Sompoch said, would not require work year-round and the staff for them could be shifted to help with other tasks that need additional workers.

With a new area-based structure, those in the central offices would primarily work as regulators and technical supporters, who would work through joint plans. The plans would be shared with those responsible for a geographic area, from directors of the regional protected area offices, to chiefs of national parks and wildlife sanctuaries, which are the work areas of the department.

There, functions such as forest restoration would be placed under the directive of the area chiefs, rather than reporting to the central offices as they have done.

Sompoch called this as a major shift in the way the department carries out its work.

“It’s the philosophy in forest protection that we should rather work through an area-based approach. With this, we would be able to respond to the needs of our forests – to be protected in a timely manner as well as our men – who need swift support and decisions from the areas.

“As many of our men as possible should be in the forests, supporting one another in the areas, rather than working at the table separately somewhere in the central offices like we do nowadays,” said Sompoch, also hoping ranger welfare would become more and more constructive as it is getting far better than the past.