Our suffering seas

Nat Sumanatemeya’s dazzling underwater shots help illustrate what’s at risk from climate change

When your dad is Sumon Sumanatemeya, a renowned professional scuba diver, you’re bound to take to water like a duck – and to the underwater world like a fish.

Nat Sumanatemeya learned the ropes from his father, but then also started taking along a camera. Today, at 48, he’s one of Thailand’s best-known underwater photographers.

“The sea has always been an important part of my life,” Nat says. “The photography combines my diving experience with what I learned studying journalism and mass communication at Thammasat University.

“I started taking pictures – on film – during the 1990s. That was before the Internet existed, so I learned from magazines and books. My favourite photographer is David Bailey, who pioneered the half-underwater photo, in which you see both the sky and the marine creatures beneath the surface.”

Nat is among 80 world-renowned photographers whose work is on display in “Beyond the Air We Breathe: Addressing Climate Change” at the Bangkok Art and Culture Centre until September 2.

The Royal Photographic Society of Thailand and the Lucie Foundation mounted the show to raise awareness about the damage being caused by greenhouse gases. The images depict a wounded earth and underline the fact that this is almost entirely humanity’s fault.

Nat points out the photos of polar explorer Sebastian Copeland and photo-journalist James Natchwey, the latter the subject of the documentary movie “War Photographer”.

“All the photos in the show reflect both the beauty of nature and the destruction caused by climate change,” says Nat.

“Copeland illustrates how it’s killing off living things at unseen and unknowable places in the Arctic and Antarctic. Natchwey deals mostly with human conflict’s effects on climate change. His pictures are both documentary and conceptual art.”

And Nat demonstrates in his photos how the beautiful underwater world is suffering from “human impact”.

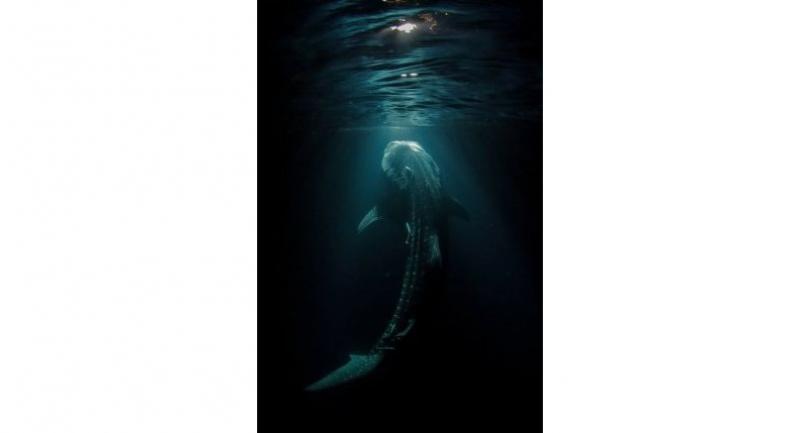

“One shot is a night scene of a whale shark off the Maldives eating plankton just beneath the surface, illuminated by the blue tail lights of a boat. It was quite a moment, last year – a scene you could only come across in a few places on Earth.”

When he was young, Nat went diving with his father off Koh Lan in Pattaya and Koh Similan in Phang Nga and in the waters of Rayong, Trat, Phuket and Krabi. Then he ventured further and further – to Malaysia, Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, South Africa, Tonga, Hawaii, Ecuador, Costa Rica, the Bahamas and the Seychelles.

“Doing documentary photography is about going beyond expectations and it depends a lot on timing and luck,” he says. “I’ve yet to face any real danger – I’m always well prepared.

“Getting a picture of a land animal, you can use a telephoto lens to get in close, but underwater you need to get within three metres of the subject to ensure good resolution and start an interaction with the animal.

“We aren’t fish – we can’t swim better or faster,” he says, “but most of my shots show marine creatures coming close to have a good look at me. They’re not hunting – they’re just curious.

“Everybody thinks the whale shark is scary and dangerous, but it’s only a predator to smaller fish. It does have its own territory and will become aggressive if something or someone gets too close. It’s the same with smaller fish, like triggerfish and anemones, which will bite if you approach during their spawning season. It’s purely defensive.”

Nevertheless, Nat does have to earn a measure of trust from his subjects.

“Tonga is one of the only places in the world where you can swim with humpback whales. The most important thing to remember when shooting an animal on land or at sea is that you must gain their trust. Fish won’t come within three metres unless you’re staying absolutely still. Even when you exhale, you try to minimise the amount of bubbles released.

Nat shows his photo taken in Krabi’s Klong Song Nam, whose water is remarkably clear. “It depicts the boundary between water and earth.”

Another shot was taken in the clean water of a lotus pond in Mexico. The clarity of the water in these images seems to buoy hope that the world isn’t suffering too badly.

But then there is still another of Nat’s picture, one of his favourites, showing a tiny fish lost inside a large plastic bag that’s drifting in the water off Koh Phi Phi. “I imagine that the little fish thinks it’s been swallowed by a jellyfish,” he says, not laughing.

An underwater photographer for 30 years, Nat has gained a great deal of knowledge and experience. Technically speaking, he relies mainly on a DSLR camera with fish-eye, wide-angle and macro lenses.

“I’m not a man for challenges – my goal is comprehension,” he says. “Some people like to take on challenges, but I think comprehending a situation is more important than pursuing risk. A challenge brings only momentary pleasure, but an understanding of something remains with you forever.

“I couldn’t be the greatest climber sitting on top of Mount Everest, or even the best underwater photographer. I’m happy to live with comprehension – to understand things about life and nature. Adventure offers a colourful life, but it’s not a life in itself.”

Nat wrote a column about his underwater excursions for "Osotho" magazine for 20 years before co-founding "Nature Explorer" in 2000 with Duangdao Suwanrangsi. Ever since that venture shut down, he’s been a freelance photographer.

Two years ago he crowdfunded his first photo book, “Okeanos”, which contains 150 of his images separated into categories – “Home”, “Survive”, “Mysterious”, “Love” and “Moment & Movement”. Its launch coincided with an exhibition of the pictures.

The end of this year will see Nat’s underwater documentary “4 Ongsa Mahasamut” broadcast on Thai PBS. It was entirely shot in Thai waters.

Nat is asked what he would advise youngsters who are considering taking the plunge into deep water – and there are bound to be more Thai kids interested after the role divers played in the Chiang Rai cave rescue.

“Diving really started to boom among younger people five years ago,” he says, “so the scene today is quite different from the way it was 30 or 35 years ago.

“To take proper care of yourself underwater, you must complete an advanced open-water dive course and have more than 50 dives,” Nat advises. “That’s essential in helping you stay calm and getting past any anxiety that arises. As well as the breathing techniques, you learn to maintain your balance and be able to stay still without moving at a given depth.”

Stay tuned: Nat is heading to Kalimantan on Borneo in Indonesia next month. There’s a huge school of barracuda waiting for him.

We punish this planet

- The exhibition “Beyond the Air We Breathe: Addressing Climate Change” continues at the Bangkok Art and Culture Centre through September 2. Admission is free.